文/汪文豪 圖/林旭陽提供

對許多五、六十歲有過務農經驗的台灣人來說,看到緬甸農村的景象:水牛犁田、赤足插秧、鐮刀採收、日曬稻穀與換工,彷彿又重拾兒時台灣農村的記憶,因為在稻米耕種全部由機械代勞的台灣來說,這些早就成為休閒農業的體驗活動。

只是,我們眼中的農業浪漫復古情懷,對以小農為主體的緬甸農業來說,卻是活生生的艱鉅考驗。農村缺乏水利與交通等公共建設,農民缺乏資金購買農機具增產,農產品缺乏良好的儲運技術,都讓緬甸稻農無論是尋求自給自足,還是提振稻米出口拚經濟,挑戰重重。

很難想像在1960年代,緬甸曾是世界上最大的稻米出口王國,鄰近的泰國與越南,都難望其項背。只是當軍政府採取極權統治讓國家陷入孤立,民間與外界隔絕,導致整體稻作技術都停留在二次大戰後期的水準。稻米出口王國的寶座,也逐漸拱手讓給泰國。

如今,緬甸走上改革開放,拚經濟的第一要務,就是要重拾往日稻米出口王國的光輝歲月。這看在曾歷經「以農業扶植工業發展」的台灣人眼裡,有著似曾相似的感覺,也代表當前看上去落後的緬甸稻作產業,對於從事精緻農業的台商或台農來說,有無窮的發展潛能與一展身手的空間。

礙於台灣與緬甸之間沒有外交關係,這一、兩年台緬的農業交流,僅有官員零星低調互訪。反倒是民間,像農機業者、從事水稻育苗的農民、溫室設備業者等,早已紛紛到緬甸投石問路,探詢合作的商機。

可惜的是,當日本、韓國是由國家與大企業聯手與緬甸政府洽談經濟合作,有計畫與目標的以團體行動到緬甸進行投資,台灣卻是零星商人或農民去闖盪,除了得自己摸索,也得承受高度的投資風險。

來自雲林元長的稻農林旭陽與台中霧峰的稻農翁良材,就曾受到在緬甸投資稻作生產的台商之邀,遠赴緬甸的第三大城「勃生(Pathein)」技術指導種稻,希望將台灣稻作產業的生產方式傳授緬甸當地農民,協助增產改善農民生活。

曾經參與創立「台灣稻農公司」的稻作從業者翁良材與林旭陽,本身是自產自銷的稻農,除了種植水稻,也兼任水稻育苗業者的身分,生產秧苗銷售給其他農民,其中翁良材還得過神農獎,兩人都可說是台灣發展精緻農業的典型代表之一。

勃生(Pathein)是緬甸的糧倉─伊洛瓦底省省會,位於緬甸國境的西南方,距離仰光西方約250公里,是緬甸最大的稻米出口中心。雖然是出口中心,但林旭陽實際看到緬甸農村現況,對於他這個曾經歷台灣早期農村生活的五年級生來說,仍然不禁感嘆。

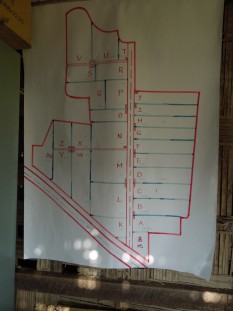

林旭陽說在台灣,農村的道路筆直,灌排水圳四通八達,田區規劃四四方方。但在緬甸農村,許多稻農的房子只由簡單的竹子與稻草組成,農村缺乏完整的灌排水路與道路規劃,耕作完全看天吃飯。雨季時,雨水多到農田變成池塘,排水不良,導致稻田泥濘,農機具難行;旱季時,因為缺乏水利設施儲存雨水,結果又面臨水量不足以增產。

除了務農環境艱困,林旭陽也發現台緬兩地耕作的差異。在台灣,秧苗都是在幼苗期就插入土中,但在緬甸,農民插秧的時程過晚,秧苗幾乎快停止分蘗才被插入土中,導致根系沒有足夠時間成長,影響營養吸收與抽穗,造成單位產量受限。林旭陽說,台灣水稻每公頃的稻穀產量可達六至十公噸的水準,但緬甸稻作每公頃稻穀產量只有三、四公噸的水準。

除此之外,緬甸農民在同一塊農地上,經常種不同品種,導致稻種混雜,也影響品質。再加上缺乏良好的稻穀烘乾與碾米設備,農民依賴日曬烘乾稻穀,但卻濕度不均,烘得太乾,導致碾米時碎粒過多,影響白米品質,外銷時只能當成加工米或飼料用途,價格低落。

與林旭陽一同前往緬甸的翁良材感嘆,緬甸的水稻品種非常優異,農民也非常純樸與認真,可惜缺乏後天良好的栽種技術與基礎建設,連烘乾與碾米設備還停留在二次大戰後期的水準。如果能夠把台灣小農發展精緻農業的技術與經驗帶來緬甸,不但可以協助稻作增產,最重要的是,讓緬甸農民可以自食其力,改善生活。

「緬甸有種植水稻最好的地理環境,卻有最窮苦的稻農,」同為農民的翁良材不可諱言,當初應緬甸台商之邀到勃生(Pathein)技術指導水稻育苗與稻種純化等技術,原本也僅是抱持姑且找尋投資機會的心態認識緬甸。

但是踏入緬甸農村看到年輕農人真摯的眼神,勤勉認真的臉龐,過著簡陋生活卻又如此認分,翁良材與林旭陽體內「惜農、憫農」的血液又沸騰了起來。

「以我們小農的財力到緬甸找尋投資機會,或許賺不了甚麼大錢,但如果能把台灣稻作技術傳授給緬甸稻農自立改善貧窮,這樣也就滿足了,」翁、林兩人如此勾勒自己的台灣稻農緬甸夢。